Publications

"Nobody does defense policy better than CSBA. Their work on strategic and budgetary topics manages to combine first-rate quality and in-depth research with timeliness and accessibility—which is why so many professionals consider their products indispensable." – Gideon Rose, Editor of Foreign Affairs, 2010-2021

The New Guns Versus Butter Debate

As the economy begins to emerge from the deepest recession since the Great Depression, the federal government faces a dire fiscal situation. In fiscal year (FY) 2009, the budget deficit rose to a record high of $1.4 trillion, and it is forecasted to reach as high as $1.6 trillion in FY 2010. These record deficits are due in no small part to increased spending on fiscal stimulus programs and a sharp reduction in tax revenues due to the recession. But underlying the current fiscal situation is a structural deficit that the economic downturn has only exacerbated. A telling indicator of this is that one of the fastest growing items in the budget is net interest on the national debt. According to OMB projections, in FY 2018 the federal government will begin spending more on net interest payments than on national defense for the first time in modern history.

The Logic and Limitations of the Nuclear Posture Review

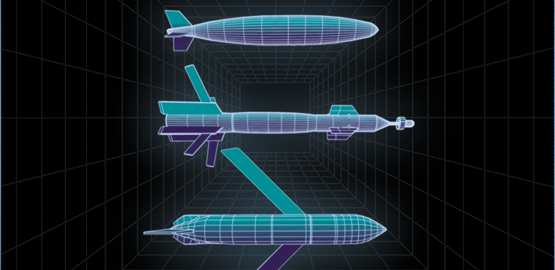

On April 6, the Department of Defense released its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which sets forth the Obama Administration’s guidance on American nuclear policy, force structure, and doctrine. The report has been highly anticipated, due in large part to President Obama’s public commitment to the goal of a nuclear weapons-free world.

Understanding the Threat of Nuclear Terrorism

Over the past several years, the prospect of a terrorist group armed with a nuclear weapon has frequently been cited as a genuine and overriding threat to the security of the United States. Moreover, press reports indicate that the forthcoming Nuclear posture review will make the goal of countering nuclear terrorism “equal to the traditional mission of deterring a strike by major powers or emerging nuclear adversaries.”1 Although the likelihood of a nuclear terrorist attack may be relatively low, the consequences of such an attack would obviously be enormous. There is, therefore, widespread agreement regarding the severity of this threat. Despite this consensus, a number of important questions remain open to debate: How real is the risk that a terrorist group could acquire or construct a functional nuclear device, and how might it attempt to do so? Which group poses the greatest threat in this regard, how has that threat changed over time, and is it currently growing or abating? What existing and prospective measures will prove most effective in preventing terrorists from obtaining a nuclear weapon, stopping them from delivering and detonating a weapon if prevention fails, and responding both at home and abroad in the event that an attack succeeds? The purpose of this backgrounder is to examine these critical issues.

Meeting the Challenge of a Proliferated World

During the early days of the Cold War, an enormous amount of thought was given to the role of nuclear weapons in the overall US defense posture. The reason for this is simple: nuclear weapons were so destructive that they fundamentally altered the competitive environment. Indeed, for several decades substantial intellectual effort was devoted to understanding the US-Soviet nuclear competition, which was a defining feature of the Cold War security environment. With the Cold War’s end, nuclear weapons proliferation has become an increasingly important issue; yet there has been comparatively little analysis of the kind that characterized the early Cold War period. Moreover, the main intellectual response to this growing danger to US security has been a renewed call for the eventual abolition of nuclear weapons. However, just as the nation’s national security leaders at the dawn of the nuclear era had to contemplate a less-than-ideal outcome of their efforts (i.e., a Soviet Union armed with large numbers of nuclear weapons, including thermonuclear weapons), so too must those who seek a world without nuclear weapons take into account the likelihood that they will not achieve this goal for decades to come, if at all.

Few Surprises in the FY 2011 Defense Budget Request

The Obama administration today unveiled its defense budget request for Fy 2011, which totals $549 billion in discretionary funding for the peacetime costs of the Department of Defense (DoD) and $4 billion in mandatory funding. In addition to the “base” budget, the administration also requests $159 billion for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) and $26 billion for national defense activities in the Department of energy and other agencies. altogether, the total national defense budget request is $739 billion for FY 2011. The budget also includes a supplemental request for $33 billion in additional funding for OCO for the remainder of FY 2010.

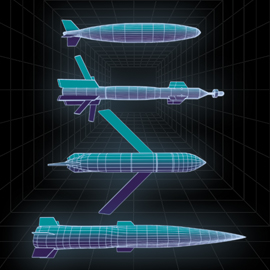

The 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review: An Initial Assessment

On February 1, 2010, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates submitted the fourth Quadrennial Defense review (QDR) report. This CSBA backgrounder provides an initial assessment of the QDR’s strategy and force planning dimensions. It finds that in general the QDR correctly identifies the major security challenges likely to confront the United States in the foreseeable future. While its six key mission areas are appropriate guides for the types of capabilities and forces DoD will need in the coming years, the QDR’s lack of operational concepts explaining how various strategic objectives can be achieved hinders the identification and prioritization of needed capabilities. In weighting its strategy and investments heavily toward addressing the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and transnational terrorism, the QDR appears to discount the urgency of investments needed to address emerging challenges, such as growing anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) threats, nuclear-armed regional powers, and sustaining access to, and use of, space and cyberspace. Thus the most significant programmatic changes in the QDR call for expanding the fleet of manned and unmanned, fixed and rotary-wing aircraft that are in highest demand in the current wars. The QDR also expands critical enablers such as logisticians and intelligence analysts for Special Operations Forces. Despite the adoption of a new force sizing construct, however, the QDR does not propose major force structure readjustments, nor does it significantly alter the allocation of resources away from legacy programs toward the QDR’s priority mission areas unrelated to current wars. Consequently, the preexisting strategy-program mismatch will persist beyond the QDR. Finally, the QDR does not adequately address the rapidly eroding US fiscal posture, the worsening financial standing of America’s key allies in Europe and Asia, or the likely consequences of the economic downturn for the united States’ long-term defense posture.