Leon Panetta has begun his tenure as secretary of defense with big challenges to manage--conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, and looming cuts in defense spending--and two clouds on the national security horizon he knows he cannot ignore.

These threatening developments are in regions long considered to be of vital interest to the United States: the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf. They will be difficult, if not impossible, to reverse.

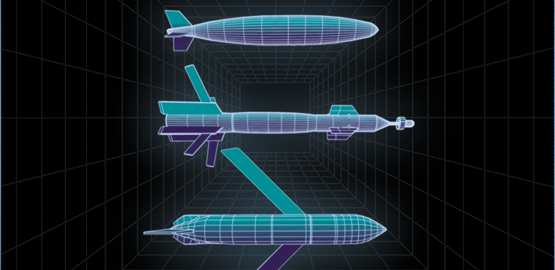

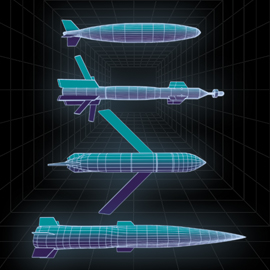

One concerns the U.S. military’s loss of its near-monopoly in precision-guided munitions, or “smart bombs.” China is fielding precision-guided ballistic and cruise missiles in increasing numbers. Their principal purpose appears to be threatening the major U.S. air bases in the Western Pacific, such as the one at Kadena on the Japanese island of Okinawa. China is also equipping its air force and navy with high-speed anti-ship cruise missiles capable of overwhelming the U.S. Navy’s carrier defenses, and it is developing a new anti-ship ballistic missile, the DF-21.

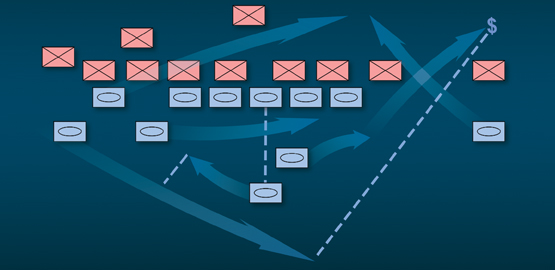

Beijing believes the U.S. military has an Achilles’ heel: its “nervous system” of battle networks. Without its satellite and fiber-optic data links, the U.S. ability to coordinate forces, target the enemy, guide weapons to their targets and maintain control over unmanned drones such as the Predator would be severely compromised. The People’s Liberation Army has in recent years fielded and tested anti-satellite lasers and rockets, and it is suspected of probing U.S. defenses with its cyber-weapons. This has led to concerns that the opening moves of a future major conflict would be against America’s information system. As Panetta put it at his confirmation hearing last month: “The next Pearl Harbor that we face could well be a cyber attack.”

Does China want war with the United States? Almost certainly not. What China does want, apparently, is to shift the military balance in the Western Pacific so that the United States will not be able to provide credible military support to longtime security partners such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

We had a word for this phenomenon during the Cold War: Finlandization. Then, the United States sought to maintain a stable military balance with the Soviet Union. One reason was that if the balance shifted in Moscow’s favor, America’s European allies might conclude that Moscow could not be resisted and would fall under Soviet sway. All of Europe would share the fate of Finland, which remained nominally independent after World War II but abided by foreign policy rules dictated in Moscow.

The second concern is Iran, which, like Beijing, is buying into the precision-guided weapons revolution. Its “poor man’s” version of China’s arsenal includes long-range ballistic missiles, supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles, smart anti-ship mines and fast attack boats to “swarm” enemy ships. The apparent goal is to turn the Persian Gulf’s constricted waters, through which 40 percent of the world’s oil shipping passes, into an Iranian lake. This challenge is compounded by Iran’s efforts to acquire a nuclear capability, which may encourage it to become more aggressive in its efforts to undermine regional security.

If Iran becomes a nuclear power, the pressure on Saudi Arabia and Turkey to follow suit might be irresistible. With ballistic missile flight times between Iran and Israel less than 10 minutes, warning capability evaporates, greatly increasing the incentive to strike first in a crisis. In these circumstances, regional stability would be severely undermined. While much thought recently has been given to achieving a world without nuclear weapons, more serious consideration should be given to how to prevent — or terminate — a “limited” nuclear war in the Middle East.

If the United States fails to respond to these challenges, the strategically vital Persian Gulf and major parts of the Western Pacific will become “no-go” zones for the U.S. military — areas where the risks of operating are prohibitively high.

The U.S. military is likely to confront these growing challenges with significantly diminished resources. The Pentagon budget is projected to be cut by $400 billion, and perhaps quite a bit more, over the next decade as Washington struggles to get its fiscal house in order. Wisely, both Panetta and his predecessor, Robert Gates, have declared that any budget cuts must be informed by a well-crafted strategy, and the Pentagon is working to craft one. A crucial test will be how well it addresses these rapidly growing risks.