As Niels Bohr famously observed, "Prediction is very difficult, especially if it's about the future." But we need not be caught entirely unaware by future events. The rapid pace of technological progression, as well as its ongoing diffusion, offer clues as to some of the likely next big things in warfare. Indeed, important military shifts have already been set in motion that will be difficult if not impossible to reverse. Sadly, these developments, combined with others in the economic, geopolitical, and demographic realms, seem likely to make the world a less stable and more dangerous place.

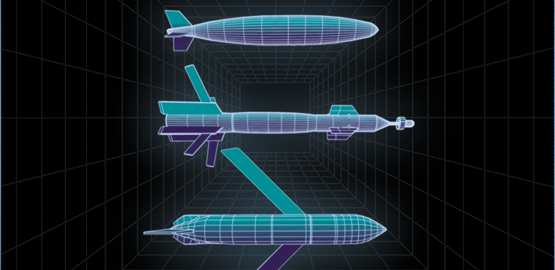

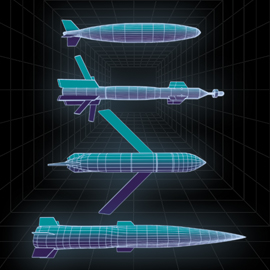

Consider, to start, the U.S. military's loss of its near monopoly in precision-guided munitions warfare, which it has enjoyed since the Gulf War two decades ago. Today China is fielding precision-guided ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as other "smart" munitions, in ever greater numbers. They can be used to threaten the few major U.S. bases remaining in the Western Pacific and, increasingly, to target American warships. Like Beijing, Iran is buying into the precision-guided weapons revolution, but at the low end, producing a poor man's version of China's capabilities, to include anti-ship cruise missiles and smart anti-ship mines. As these trends play out we could find that by the beginning of the next decade, major parts of the Western Pacific, as well as the Persian Gulf, become no-go zones for the U.S. military: areas where the risks of operating are prohibitively high.

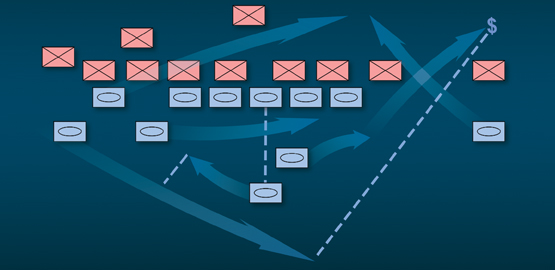

Even nonstate groups are getting into the game. During its war with Israel in 2006, Hezbollah fired more than 4,000 relatively inaccurate RAMM projectiles -- rockets, artillery, mortars, and missiles -- into Israel, leading to the evacuation of at least 300,000 Israelis from their homes and causing significant disruption to that country's economy. Out of these thousands of munitions, only a few drones and anti-ship cruise missiles were guided. But as the proliferation of guided munitions -- G-RAMM weapons -- continues, irregular warfare will be transformed to the point that the roadside bomb threats that the United States has spent tens of billions of dollars defending against in Iraq and Afghanistan may seem trivial by comparison.

The spread of nuclear weapons to the developing world is equally alarming. If Iran becomes a nuclear power, the pressure on the leading Arab states as well as Turkey to follow suit is likely to prove irresistible. With ballistic-missile flight times between states in the region measured in single-digit minutes, the stability of the global economy's energy core would be exceedingly fragile.

But the greatest danger of a catastrophic attack on the U.S. homeland will likely come not from nuclear-armed missiles, but from cyberattacks conducted at the speed of light. The United States, which has an advanced civilian cyberinfrastructure but prohibits its military from defending it, will prove a highly attractive target, particularly given that the processes for attributing attacks to their perpetrators are neither swift nor foolproof. Foreign powers may already have prepositioned "logic bombs" -- computer code inserted surreptitiously to trigger a future malicious effect -- in the U.S. power grid, potentially enabling them to trigger a prolonged and massive future blackout.

As in the cyber realm, the very advances in biotechnology that appear to offer such promise for improving the human condition have the potential to inflict incalculable suffering. For example, "designer" pathogens targeting specific human subgroups or designed to overcome conventional antibiotics and antiviral countermeasures now appear increasingly plausible, giving scientists a power once thought to be the province of science fiction. As in the cyber realm, such advances will rapidly increase the potential destructive power of small groups, a phenomenon that might be characterized as the "democratization of destruction."

International stability is also increasingly at risk owing to structural weaknesses in the global economic system. Commercial man-made satellites, for instance, offer little, if any, protection against the growing threat of anti-satellite systems, whether ground-based lasers or direct-ascent kinetic-kill vehicles. The Internet was similarly constructed with a benign environment in mind, and the progression toward potential sources of single-point system failure, in the forms of both common software and data repositories like the "cloud," cannot be discounted.

Then there is the undersea economic infrastructure, primarily located on the world's continental shelves. It provides a substantial portion of the world's oil and natural gas, while also hosting a web of cables connecting the global fiber-optic grid. The value of the capital assets on the U.S. continental shelves alone runs into the trillions of dollars. These assets -- wellheads, pumping stations, cables, floating platforms -- are effectively undefended.

As challenges to the global order increase in scale and shift in form, the means for addressing them are actually declining. The age of austerity is upon us, and it seems likely if not certain that the U.S. military will confront these growing challenges with relatively diminished resources. The Pentagon's budget is scheduled for $400 billion or more in cuts over the next decade. Europe certainly cannot be counted on to pick up the slack. Nor is it clear whether rising great powers such as Brazil and India will try to fill the void.

With technology advancing so rapidly, might the United States attempt to preserve its military dominance, and international stability, by developing new sources of military advantage? Recently, there have been dramatic innovations in directed energy -- lasers and particle beams -- that could enable major advances in key mission areas. But there are indications that competitors, China in particular, are keeping pace and may even enjoy an advantage.

The United States has the lead in robotics -- for now. While many are aware of the Predator drones used in the war against radical Islamist groups, robots are also appearing in the form of undersea craft and terrestrial mechanical "mules" used to move equipment. But the Pentagon will need to prove better than its rivals at exploiting advances in artificial intelligence to enhance the performance of its unmanned systems. The U.S. military will also need to make its robot crafts stealthier, reduce their vulnerability to more sophisticated rivals than the Taliban, and make their data links more robust in order to fend off efforts to disable them.

The bottom line is that the United States and its allies risk losing their military edge, and new threats to global security are arising faster than they can counter them. Think the current world order is fragile? In the words of the great Al Jolson, "You ain't seen nothin' yet."