Many ships are sailing on cruises far beyond the once-standard six or seven months, and Navy leaders are eager to make these long and often unpredictable deployments the exception.

They’ve developed a plan to lock in eight-month deployments, but a mounting body of testimony from Navy officials suggests that the plan may soon be another victim of budget battles — and sailors will end up paying the price.

At the center of the dilemma is the aircraft carrier George Washington, which will be retired early unless lawmakers lift heavy sequestration spending cuts set to take effect in 2016. With no sign they will and uncertainties about when the first of the new supercarrier class will be ready to deploy, experts say nine-to-10-month deployments could be common for fleet sailors.

That’s a worst-case scenario for Navy leaders.

“We need 11 aircraft carriers, and we’re very cognizant of that fact,” Navy Secretary Ray Mabus said in a March hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee. “We need those 11 carriers for the operations tempo and for the stress that is put on the other carriers should we lose one.”

At issue is about $6 billion, the cost to refuel the 22-year-old GW, allowing it to sail out the remaining 28 years it was built to serve.

A bipartisan budget deal permitted the services to escape heavy spending cuts in fiscal years 2014 and 2015, but without a similar deal before 2016, the Navy says it will be forced to mothball or scrap the GW.

That, in turn, could toss the new eight-month deployment plan overboard by 2019 and most likely much sooner, defense experts and lawmakers say.

“A fleet of 10 aircraft carriers will eventually be forced to undertake nine- and 10-month deployments,” said Rep. Randy Forbes, R-4th D. who chairs the House Armed Services Committee’s seapower and projection forces panel, in a statement.

'Not sustainable'

The fleet’s top boss has been very clear: Nine- and 10-month deployments are not what the Navy wants. But that’s where many cruises are.

The George H.W. Bush carrier strike group — composed of the Bush, Carrier Air Wing 8, cruiser Philippine Sea and destroyers Truxtun and Roosevelt — left in February for what’s set to be one of the longest CSG deployments in years.

“We just sent Bush out on a 9½-month deployment; that’s not a sustainable model,” said Adm. Bill Gortney, the head of Fleet Forces Command, in a recent interview with Defense News, a sister publication of Navy Times. “We want to get it to eight months, and we think that’s sustainable over a three-year period,” he continued, referring to the new 36-month deployment cycle that carriers will start later this year.

This plan will also eventually cover the amphibious fleet, which also has seen some extended floats.

But scrapping the GW will throw a wrench in those plans when the refueled flattop was supposed to rejoin the fleet.

“We can do that with one fewer carrier, until GW was supposed to come out of a refueling cycle,” Gortney continued. “Now she’s not there, and we will go back to 9½-month deployments.”

Gortney’s eight-month deployment plan, the Optimized Fleet Response Plan, is scheduled to begin with the carrier Harry S. Truman, which returned to Norfolk in April from a nine-month deployment.

The idea behind it is to give sailors a more predictable schedule, which the Navy says will pay dividends in the form of well-maintained ships and happier crews.

The payoff for sailors is a significant increase in dwell time. Gortney said an eight-month deployment is on the “ragged edge” of what’s acceptable for sailors but that they can expect as much as 68 percent of the 36-month schedule to be tied up to a pier, as long as they’re not deployed during the 14-month sustainment period after the ship returns from a cruise.

Locking in eight-month deployments that follow a predictable schedule is a difficult challenge that may prove impossible without the GW or a dramatic drop in deployment orders for flattops.

That’s exceedingly unlikely, said Forbes, whose subcommittee oversees the Navy.

“While the fleet is shrinking, the demands on our Navy are only growing, requiring fewer ships to execute more missions,” Forbes said. “The morale and retention of our personnel, and thus the security of this country, are bound to suffer.”

Forbes is not alone in his concerns. Gortney, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jon Greenert and Chief of Naval Personnel Vice Adm. Bill Moran have all spoken out against the toll that long deployments take on sailors and their families.

It remains unclear if those concerns will be enough.

Carrier shuffle

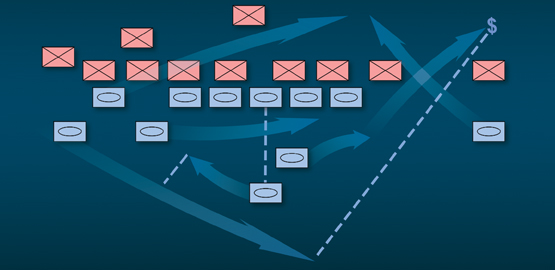

America’s national security posture demands that we have two carriers deployed at any time, one in the Pacific and the other in the Middle East.

The Pentagon sets these levels based on requests from the combatant commanders, four-star officials who oversee missions around the globe. It’s the Navy’s job to make sure the ships are manned and ready when they get the call.

Budget cuts have compounded maintenance issues, but those deployment levels haven’t changed since 2013, when the Pentagon lowered the 5th Fleet carrier presence from two to one.

Bryan Clark, a retired Navy commander who is now a defense expert with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments in Washington, said these combatant commanders aren’t likely to lighten the requirements any time soon.

The current deployment cycle assumes that one of the Navy’s carriers is refueling at all times, a process that takes about 3½ years. The carrier Lincoln began its overhaul in March 2013, and GW is next up. It would be scheduled to come out in 2019.

But if the Navy retires GW instead, the number of deployable carriers drops down to nine, and that would put sailors back on the nine-month-plus plan.

The Navy is already at 10 carriers while it awaits delivery of the first-in-class Gerald R. Ford. But the delivery has been pushed back and the Navy is now expecting delivery in early 2016 with the ship being available for deployment in 2017.

Reports by government watchdogs, however, say the Navy won’t know when the Ford will be ready to deploy until it shakes out the bugs in all the new technology on board, including revolutionary new systems like electromagnetic plane catapults.

“If the Ford can deploy in 2017, the effects of losing the GW would not be felt until 2019, when it would have been scheduled to come out of refueling,” Clark said in a phone interview. “But that assumes that the Ford will be ready to deploy. I think with all the new technologies on board, the Navy will be challenged to have it deploy so quickly.

“So if you have deployments steadily getting longer prior to 2019 without the GW, the problem gets even worse if the Ford isn’t ready/.../”